The internal troubles connected with the "Disk-worship" had for about forty years distracted the attention of the Egyptians from their Asiatic possessions; and this circumstance had favoured the development of a highly important power in Western Asia. The Hittites, whose motto was "reculer pour mieux sauter," having withdrawn themselves from Syria during the time of the Egyptian attacks, retaining, perhaps, their hold on Carchemish (Jerabus), but not seeking to extend themselves further southward, took heart of grace when the Egyptian expeditions ceased, and descending from their mountain fastnesses to the Syrian plains and vales, rapidly established their dominion over the regions recently conquered by Thothmes I. and Thothmes III. Without absorbing the old native races, they reduced them under their sway, and reigned as lords paramount over the entire region between the Middle Euphrates and the Mediterranean, the Taurus range and the borders of Egypt. The chief of the subject races were the Kharu, in the tract bordering upon Egypt; the Rutennu, in Central and Northern Palestine; and in Southern Cœlesyria, the Amairu or Amorites. The Hittites themselves occupied the lower Cœlesyrian valley, and the tract reaching thence to the Euphrates. They were at this period so far centralized into a nation as to have placed themselves under a single monarch; and about the time when Egypt had recovered from the troubles caused by the "Disk-worshippers," and was again at liberty to look abroad, Saplal, Grand-Duke of Khita, a great and puissant sovereign, sat upon the Hittite throne.

Saplal's power, and his threatening attitude on the north-eastern border of Egypt, drew upon him the jealousy of Ramesses I., father of the great Seti, and (according to the prevalent tradition) founder of the "nineteenth dynasty." To defend oneself it is often best to attack, and Ramesses, taking this view, in his first or second year plunged into the enemy's dominions. He had the plea that Palestine and Syria, and even Western Mesopotamia, belonged of right to Egypt, which had conquered them by a long series of victories, and had never lost them by any defeat or disaster. His invasion was a challenge to Saplal either to fight for his ill-gotten gains, or to give them up. The Hittite king accepted the challenge, and a short struggle followed with an indecisive result. At its close peace was made, and a formal treaty of alliance drawn out. Its terms are unknown; but it was probably engraved on a silver plate in the languages of the two powers—the Egyptian hieroglyphics, and the now well-known Hittite picture-writing—and set up in duplicate at Carchemish and Thebes.

A brief pause followed the conclusion of the first act of the drama. On the opening of the second act we find the dramatis personæ changed. Saplal and Ramesses have alike descended into the grave, and their thrones are occupied respectively by the son of the one and the grandson of the other. In Egypt, Seti-Menephthah I., the Sethos of Manetho, has succeeded his father, Ramesses I.; in the Hittite kingdom, Saplal has left his sceptre to his grandson Mautenar, the son of Marasar, who had probably died before his father. Two young and inexperienced princes confront one the other in the two neighbour lands, each distrustful of his rival, each covetous of glory, each hopeful of success if war should break out. True, by treaty the two kings were friends and allies—by treaty the two nations were bound to abstain from all aggression by the one upon the other: but such bonds are like the "green withes" that bound Samson, when the desire to burst them seizes those upon whom they have been placed. Seti and Mautenar were at war before the latter had been on the throne a year, and their swords were at one another's throats. Seti was, apparently, the aggressor. We find him at the head of a large army in the heart of Syria before we could have supposed that he had had time to settle himself comfortably in his father's seat.

Mautenar was taken unawares. He had not expected so prompt an attack. He had perhaps been weak enough to count on his adversary's good faith, or, at any rate on his regard for appearances. But Seti, as a god upon earth, could of course do no wrong, and did not allow himself to be trammelled by the moral laws that were binding upon ordinary mortals. He boldly rushed into war at the first possible moment, crossed the frontier, and having chastised the Shasu, who had recently made an invasion of his territory, fell upon the Kharu, or Southern Syrians, and gave them a severe defeat near Jamnia in the Philistine country. He then pressed forward into the country of the Rutennu, overcame them in several pitched battles, and, assisted by a son who fought constantly at his side, slaughtered them almost to extermination. His victorious progress brought him, after a time, to the vicinity of Kadesh, the important city on the Orontes which, a century earlier, had been besieged and taken by the Great Thothmes. Kadesh was at this time in possession of the Amorites, who were tributary to the Khita (Hittites) and held the great city as their subject allies. Seti, having carefully concealed his advance, came upon the stronghold suddenly, and took its defenders by surprise. Outside the city peaceful herdsmen were pasturing their cattle under the shade of the trees, when they were startled by the appearance of the Egyptian monarch, mounted on his war-chariot drawn by two prancing steeds. At once all was confusion: every one sought to save himself; the herds with their keepers fled in wild panic, while the Egyptians plied them with their arrows. But the garrison of the town resisted bravely: a portion sallied from the gates and met Seti in the open field, but were defeated with great slaughter; the others defended themselves behind the walls. But all was in vain. The disciplined troops of Egypt stormed the key of Northern Syria, and the whole Orontes valley lay open to the conqueror.

Hitherto the Hittites had not been engaged in the struggle. Attacked at a disadvantage, unprepared, they had left their subject allies to make such resistance as they might find possible, and had reserved themselves for the defence of their own country. Mautenar had, no doubt, made the best preparations of which circumstances admitted—he had organized his forces in three bodies, "on foot, on horseback, and in chariots." At the head of them, he gave battle to the invaders so soon as they attacked him in his own proper country, and a desperate fight followed, in which the Egyptians, however, prevailed at last. The Hittites received a "great overthrow." The song of triumph composed for Seti on the occasion declared: "Pharaoh is a jackal which rushes leaping through the Hittite land; he is a grim lion exploring the hidden ways of all regions; he is a powerful bull with a pair of sharpened horns. He has struck down the Asiatics; he has thrown to the ground the Khita; he has slain their princes; he has overwhelmed them in their own blood; he has passed among them as a flame of fire; he has brought them to nought."

The victory thus gained was followed by a treaty of peace. Mautenar and Seti agreed to be henceforth friends and allies, Southern Syria being restored to Egypt, and Northern Syria remaining under the dominion of the Hittites, probably as far as the sources of the Orontes river. A line of communication must, however, have been left open between Egypt and Mesopotamia, for Seti still exercised authority over the Naïri, and received tribute from their chiefs. He was also, by the terms of the treaty, at liberty to make war on the nations of the Upper Syrian coast, for we find him reducing the Tahai, who bordered on Cilicia, without any disturbance of his relations with Mautenar. The second act in the war between the Egyptians and the Hittites thus terminated with an advantage to the Egyptians, who recovered most of their Asiatic possessions, and had, besides, the prestige of a great victory.

The third act was deferred for a space of some thirty-five years, and fell into the reign of Ramesses II., Seti's son and successor. Before giving an account of it, we must briefly touch the other wars of Seti, to show how great a warrior he was, and mention one further fact in his warlike policy indicative of the commencement of Egypt's decline as a military power. Seti, then, had no sooner concluded his peace with the great power of the North, than he turned his arms against the West and South, invading, first of all, "the blue-eyed, fair-skinned nation of the Tahennu," who inhabited the North African coast from the borders of Egypt to about Cyrene, and engaging in a sharp contest with them. The Tahennu were a wild, uncivilized people, dwelling in caves, and having no other arms besides bows and arrows. For dress they wore a long cloak or tunic, open in front; and they are distinguished on the Egyptian monuments by wearing two ostrich feathers and having all their hair shaved excepting one large lock, which is plaited and hangs down on the right side of the head. This unfortunate people could make only a poor resistance to the Egyptian trained infantry and powerful chariot force. They were completely defeated in a pitched battle; numbers of the chiefs were made prisoners, while the people generally fled to their caves, where they remained hidden, "like jackals, through fear of the king's majesty." Seti, having struck terror into their hearts, passed on towards the south, and fiercely chastised the Cushites on the Upper Nile, who during the war with the Hittites had given trouble, and showed themselves inclined to shake off the Egyptian yoke. Here again he was successful; the negroes and Cushites submitted after a short struggle; and the Great King returned to his capital victorious on all sides—"on the south to the arms of the Winds, and on the north to the Great Sea."

Seti was not dazzled with his military successes. Notwithstanding his triumphs in Syria, he recognized the fact that Egypt had much to fear from her Asiatic neighbours, and could not hope to maintain for long her aggressive attitude in that quarter. Without withdrawing from any of the conquered countries, while still claiming their obedience and enforcing the payment of their tributes, he began to made preparation for the changed circumstances which he anticipated by commencing the construction of a long wall on his north-eastern frontier, as a security against invasion from Asia. This wall began at Pelusium, and was carried across the isthmus in a south-westerly direction by Migdol to Pithom, or Heroopolis, where the long line of lagoons began, which were connected with the upper end of the Red Sea. It recalls to the mind of the historical student the many ramparts raised by nations, in their decline, against aggressive foes—as the Great Wall of China, built to keep off the Tartars; the Roman wall between the Rhine and Danube, intended to restrain the advance of the German tribes; and the three Roman ramparts in Great Britain, built to protect the Roman province from its savage northern neighbours. Walls of this kind are always signs of weakness; and when Seti began, and Ramesses II. completed, the rampart of Egypt, it was a confession that the palmy days of the empire were past, and that henceforth she must look forward to having to stand, in the main, on the defensive.

Before acquiescing wholly in this conclusion, Ramesses II., who, after reigning conjointly with his father for several years, was now sole king, resolved on a desperate and prolonged effort to re-assert for Egypt that dominant position in Western Asia which she had held and obtained under the third Thothmes. Mautenar, the adversary of Seti, appears to have died, and his place to have been taken by his brother, Khita-sir, a brave and enterprizing monarch. Khita-sir, despite the terms of alliance on which the Hittites stood with Egypt, had commenced a series of intrigues with the nations bordering on Upper Syria, and formed a confederacy which had for its object to resist the further progress of the Egyptians, and, if possible, to drive them from Asia. This confederacy embraced the Naïri, or people of Western Mesopotamia, reckoned by the Egyptians among their subjects; the Airatu or people of Aradus; the Masu or inhabitants of the Mous Masius; the Leka, perhaps Lycians; the inhabitants of Carchemish, of Kadesh on the Orontes, of Aleppo, Anaukasa, Akarita, &c.—all warlike races, and accustomed to the use of chariots. Khitasir's proceedings, having become known to Ramesses, afforded ample grounds for a rupture, and quite justified him in pouring his troops into Syria, and doing his best to meet and overcome the danger which threatened him. Unaware at what point his enemy would elect to meet him, he marched forward cautiously, having arranged his troops in four divisions, which might mutually support each other. Entering the Cœlesyrian valley from the south, he had proceeded as far as the lake of Hems, and neighbourhood of Kadesh, before he received any tidings of the position taken up by the confederate army. There his troops captured two of the enemy's scouts, and on questioning them were told that the Hittite army had been at Kadesh, but had retired on learning the Egyptian's advance and taken up a position near Aleppo, distant nearly a hundred miles to the north-east. Had Ramesses believed the scouts, and marched forward carelessly, he would have fallen into a trap, and probably suffered defeat; for the whole confederate army was massed just beyond the lake, and there lay concealed by the embankment which blocks the lake at its lower end. But the Egyptian king was too wary for his adversary. He ordered the scouts to be examined by scourging, to see if they would persist in their tale, whereupon they broke down and revealed the true position of the army. The battle had thus the character of a regular pitched engagement, without surprise or other accident on either side. Khitasir, finding himself foiled, quitted his ambush, and marched openly against the Egyptians, with his troops marshalled in exact and orderly array, the Hittite chariots in front with their lines carefully dressed, and the auxiliaries and irregulars on the flanks and rear. Of the four divisions of the Egyptian army, one seems to have been absent, probably acting as a rear-guard; Ramesses, with one, marched down the left bank of the stream, while the two remaining divisions proceeded along the right bank, a slight interval separating them. Khitasir commenced the fight by a flank movement to the left, which brought him into collision with the extreme Egyptian right, "the brigade of Ra," as it was called, and enabled him to engage that division separately. His assault was irresistible. "Foot and horse of King Ramesses," we are told, "gave way before him," the "brigade of Ra" was utterly routed, and either cut to pieces or driven from the field. Ramesses, informed of this disaster, endeavoured to cross the river to the assistance of his beaten troops; but, before he could effect his purpose, the enemy had anticipated him, had charged through the Orontes in two lines, and was upon him. The adverse hosts met. The chariot of Ramesses, skilfully guided by his squire, Menna, seems to have broken through the front line of the Hittite chariot force; but his brethren in arms were less fortunate, and Ramesses found himself separated from his army, behind the front line and confronted by the second line of the hostile chariots, in a position of the greatest possible danger. Then began that Homeric combat, which the Egyptians were never tired of celebrating, between a single warrior on the one hand, and the host of the Hittites, reckoned at two thousand five hundred chariots, on the other, in which Ramesses, like Diomed or Achilles, carried death and destruction whithersoever he turned himself. "I became like the god Mentu," he is made to say; "I hurled the dart with my right hand, I fought with my left hand; I was like Baal in his fury against them. I had come upon two thousand five hundred pairs of horses; I was in the midst of them; but they were dashed in pieces before my steeds. Not one of them raised his hand to fight; their heart shrank within them; their limbs gave way, they could not hurl the dart, nor had they strength to thrust with the spear. As crocodiles fall into the water, so I made them fall; they tumbled headlong one over another. I killed them at my pleasure, so that not one of them looked back behind him, nor did any turn round. Each fell, and none raised himself up again."

The temporary isolation of the monarch, which is the main point of the heroic poem of Pentaour, and which Ramesses himself recorded over and over again upon the walls of his magnificent constructions, must no doubt be regarded as a fact; but it is not likely to have continued for more than a few minutes. The minutes may have seemed as hours to the king; and there may have been time for him to perform several exploits. But we may be sure that, when his companions found that he was lost to their sight, they at once made frantic efforts to recover him, dead or alive; they forced openings in the first Hittite chariot line, and sped to the rescue of their sovereign. He had, perhaps, already emptied many chariots of the second line, which was paralysed by his audacity; and his companions found it easy to complete the work which he had begun. The broken second line turned and fled; the confusion became general; a headlong flight carried the entire host to the banks of the Orontes, into which some precipitated themselves, while others were forced into the water by their pursuers. The king of Khirabu (Aleppo) was among these, and was with great difficulty drawn out by his friends, exhausted and half dead, when he reached the eastern shore. But the great bulk of the Hittite army perished, either in the battle or in the river. Among the killed and wounded were Grabatasa, the charioteer of Khitasir; Tarakennas, the commander of the cavalry; Rabsuna, another general; Khirapusar, a royal secretary; and Matsurama, a brother of the Hittite king.

On the next day the battle was renewed; but, after a short time, Khitasir retired, and sent a humble embassy to the camp of his adversary to implore for peace. Ramesses held a council of war with his generals, and by their advice agreed to accept the submission made to him, and, without entering into any formal engagement, to withdraw his army and return to Egypt. It seems probable that his victory had cost him dear, and that he was not in a condition to venture further from his resources, or to affront new dangers in a difficult, and to him unknown, region.

Experience tells us that it is one thing to gain a battle, quite another to be successful in the result of a long war. Whatever glory Ramesses obtained by the battle of Kadesh, and the other victories which he claims to have won in the Syrian campaigns of several succeeding years, it is certain that he completely failed to break the power of the Hittites, and that he was led in course of time to confess his failure, and to adopt a policy of conciliation towards the people which he found himself unable to subdue. Sixteen years after the battle of Kadesh he concluded a solemn treaty with Khitasir, which was engraved on silver and placed under the most sacred sanctions, whereby an exact equality was established between the high contracting powers. Each nation bound itself under no circumstances to attack the other; each promised to give aid to the other, if requested, in case of its ally being attacked; each pledged itself to the extradition both of criminals flying from justice and of any other subjects wishing to change their allegiance; each stipulated for an amnesty of offences in the case of all persons thus surrendered. Thirteen years after the conclusion of the treaty the close alliance between the two powers was further cemented by a marriage, which, by giving the two dynasties common interests, greatly strengthened the previously existing bond. Ramesses requested and received in marriage a daughter of Khitasir in the thirty-fourth year of his sole reign, when he had borne the royal title for forty-six years. He thus became the son-in-law of his former adversary, whose daughter was thenceforth recognized as his sole legitimate queen.

A considerable change in the relations of Egypt to her still remaining Asiatic dependencies accompanied this alteration in the footing upon which she stood with the Hittites. "The bonds of their subjection became much less strict than they had been under Thothmes III.; prudential motives constrained the Egyptians to be content with very much less—with such acknowledgments, in fact, as satisfied their vanity, rather than with the exercise of any real power." From and after the conclusion of peace and alliance between Ramesses and Khitasir, Egyptian influence in Asia grew vague, shadowy, and discontinuous. At long intervals monarchs of more enterprize than the ordinary run asserted it, and a brief success generally crowned their efforts; but, speaking broadly, we may say that her Asiatic dominion was lost, and that Egypt became once more an African power, confined within nearly her ancient limits.

If, from a military point of view, the decline of Egypt is to be dated from the reigns, partly joint reigns, of Seti I. and Ramesses II., from the stand-point of art the period must be pronounced the very apogee of Egyptian greatness. The architectural works of these two monarchs transcend most decidedly all those of all other Pharaohs, either earlier or later. No single work, indeed, of either king equals in mass either the First or the Second Pyramid; but in number, in variety, in beauty, in all that constitutes artistic excellence, the constructions of Seti and Ramesses are unequalled, not only among Egyptian monuments, but among those of all other nations. Greece is, of course, unapproachable in the matter of sculpture, whether in the way of statuary, or of high or low relief; but, apart from this, Egypt in her architectural works will challenge comparison with any country that ever existed, or any people that ever gave itself to the embodiment of artistic conceptions in stone or marble. And Egyptian architecture culminated under Seti and his son Ramesses. The greatest of all Seti's works was his pillared hall at Karnak, the most splendid single chamber that has ever been built by any architect, and, even in its ruins, one of the grandest sights that the world contains. Seti's hall is three hundred and thirty feet long, by one hundred and seventy feet broad, having thus an internal area of fifty-six thousand square feet, and covers, together with its walls and pylons, an area of eighty-eight thousand such feet, or a larger space than that covered by the Dom of Cologne, the largest of all the cathedrals north of the Alps. It was supported by one hundred and sixty-four massive stone columns, which were divided into three groups—twelve central ones, each sixty-six feet high and thirty-three feet in circumference, formed the main avenue down its midst; while on either side, two groups of sixty-one columns, each forty-two feet high and twenty-seven round, supported the huge wings of the chamber, arranged in seven rows of seven each, and two rows of six. The whole was roofed over with solid blocks of stone, the lighting being, as in the far smaller hall of Thothmes III., by means of a clerestory. The roof and pillars and walls were everywhere covered with painted bas-reliefs and hieroglyphics, giving great richness of effect, and constituting the whole building the most magnificent on which the eye of man has ever rested. Fergusson, the best modern authority on architecture, says of it: "No language can convey an idea of its beauty, and no artist has yet been able to reproduce its form so as to convey to those who have not seen it an idea of its grandeur. The mass of its central piers, illumined by a flood of light from the clerestory, and the smaller pillars of the wings gradually fading into obscurity, are so arranged and lighted as to convey an idea of infinite space; at the same time the beauty and massiveness of the forms, and the brilliancy of their coloured decorations, all combine to stamp this as the greatest of man's architectural works, but such a one as it would be impossible to reproduce, except in such a climate, and in that individual style, in which and for which it was created."[24]

As Seti constructed the most wonderful of all the palatial buildings which Egypt produced, so he also constructed what is, on the whole, the most wonderful of the tombs. The pyramids impose upon us by their enormity, and astonish by the engineering skill shown in their execution; but they embody a single simple idea; they have no complication of parts, no elaboration of ornament; they are taken in at a glance; they do not gradually unfold themselves, or furnish a succession of surprises. But it is otherwise with the rock-tombs, whereof Seti's is the most magnificent The rock-tombs are "gorgeous palaces, hewn out of the rock, and painted with all the decorations that could have been seen in palaces." They contain a succession of passages, chambers, corridors, staircases, and pillared halls, each further removed from the entrance than the last, and all covered with an infinite variety of the most finished and brilliant paintings. The tomb of Seti contains three pillared halls, respectively twenty-seven feet by twenty-five, twenty-eight feet by twenty-seven, and forty-three feet by seventeen and a half; a large saloon with an arched roof, thirty feet by twenty-seven; six smaller chambers of different sizes; three staircases, and two long corridors. The whole series of apartments, from end to end of the tomb, is continuously ornamented with painted bas-reliefs. "The idea is that of conducting the king to the world of death. The further you advance into the tomb, the deeper you become involved in endless processions of jackal-headed gods, and monstrous forms of genii, good and evil; and the goddess of Justice, with her single ostrich feather; and barges carrying mummies, raised aloft over the sacred lake; and mummies themselves; and, more than all, everlasting convolutions of serpents in every possible form and attitude—human-legged, human-headed, crowned, entwining mummies, enwreathing or embraced by processions, extending down whole galleries, so that meeting the head of a serpent at the top of a staircase, you have to descend to its very end before you reach his tail. At last you arrive at the close of all—the vaulted hall, in the centre of which lies the immense alabaster sarcophagus, which ought to contain the body of the king. Here the processions, above, below, and around, reach their highest pitch—meandering round and round—white, and black, and red, and blue—legs and arms and wings spreading in enormous forms over the ceilings; and below lies the sarcophagus itself."[25]

The greatest of the works of Ramesses are of a different description, and are indicative of that inordinate vanity which is the leading feature of his character. They are colossal images of himself. Four of these, each seventy feet in height, form the façade of the marvellous rock-temple of Ipsambul—"the finest of its class known to exist anywhere"—and constitute one of the most impressive sights which the world has to offer. There stands the Great King, four times repeated, silent, majestic, superhuman—with features marked by profound repose and tranquillity, touched perhaps with a little scorn, looking out eternally on the grey-white Nubian waste, which stretches far away to a dim and distant horizon. Here, as you sit on the deep pure sand, you seem to see the monarch, who did so much, who reigned so long, who covered, not only Egypt, but Nubia and Ethiopia with his memorials. "You can look at his features inch by inch, see them not only magnified to tenfold their original size, so that ear and mouth and nose, and every link of his collar, and every line of his skin, sinks into you with the weight of a mountain; but those features are repeated exactly the same three times over—four times they once were, but the upper part of the fourth statue is gone. Look at them as they emerge—the two northern figures—from the sand which reaches up to their throats; the southernmost, as he sits unbroken, and revealed from the top of his royal helmet to the toe of his enormous foot"[26] Look at them, and remember that you have here portrait-statues of one of the greatest of the kings of the Old World, of the world that was "old" when Greece and Rome were either unborn or in their swaddling clothes; portrait-statues, moreover, of the king who, if either tradition or chronology can be depended on, was the actual great oppressor of Israel—the king who sought the life of Moses—the king from whom Moses fled, and until whose death he did not dare to return out of the land of Midian.

According to the almost unanimous voice of those most conversant with Egyptian antiquities, the "great oppressor" of the Hebrews was this Ramesses. Seti may have been the originator of the scheme for crushing them by hard usage, but, as the oppression lasted close upon eighty years (Ex. ii, I; vii. 7), it must have covered at least two reigns, so that, if it began under Seti, it must have continued under his son and successor. The bricks found at Tel-el-Maskoutah show Ramesses as the main builder of Pithom (Pa-Tum), and the very name indicates that he was the main builder of Raamses (Pa-Ramessu). We must thus ascribe to him, at any rate, the great bulk of that severe and cruel affliction, which provoked Moses (Ex. ii, 12), which made Israel "sigh" and "groan" (ib. 23, 24), and on which God looked down with compassion (ib. iii. 7). It was he especially who "made their lives bitter in mortar, and in brick, and in all manner of service in the field"—service which was "with rigour." Ramesses was a builder on the most extensive scale. Without producing any single edifice so perfect as the "Pillared Hall of Seti," he was indefatigable in his constructive efforts, and no Egyptian king came up to him in this respect. The monuments show that he erected his buildings chiefly by forced labour, and that those employed on them were chiefly foreigners. Some have thought that the Hebrews are distinctly mentioned as employed by him on his constructions under the term "Aperu," or "Aperiu"; but this view is not generally accepted. Still, "the name is so often used for foreign bondsmen engaged in the very work of the Hebrews, and especially during the oppression, that it is hard not to believe it to be a general term in which they are included, though it does not actually describe them."[27]

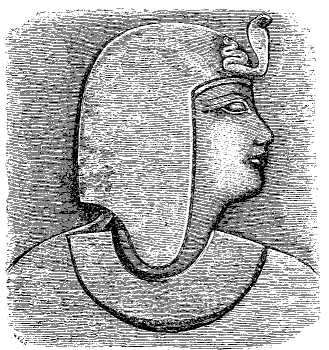

HEAD OF SETI

HEAD OF SETI

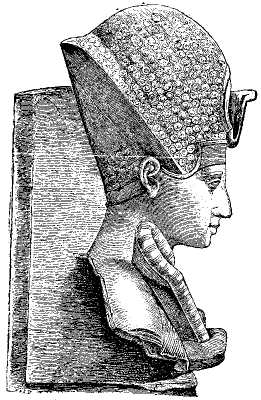

BUST OF RAMESSES II.

BUST OF RAMESSES II.

The physiognomies of Seti I. and Ramesses II., as represented on the sculptures,[28] offer a curious contrast Seti's face is thoroughly African, strong, fierce, prognathous, with depressed nose, thick lips, and a heavy chin. The face of Ramesses is Asiatic. He has a good forehead, a large, well-formed, slightly aquiline nose, a well-shaped mouth, with lips that are not too full, a small delicate chin, and an eye that is thoughtful and pensive. We may conclude that Seti was of the true Egyptian race, with perhaps an admixture of more southern blood; while Ramesses, born of a Semitic mother, inherited through her Asiatic characteristics, and, though possessing less energy and strength of character than his father, had a more sensitive temperament, a wider range of taste, and a greater inclination towards peace and tranquillity. His important wars were all concluded within the limit of his twenty-first year, while his entire reign was one of sixty-seven years, during fifty of which he held the sole sovereignty. Though he left the fame of a great warrior behind him, his chief and truest triumphs seem to have been those of peace—the Great Wall for the protection of Egypt towards the east, with its strong fortresses and "store-cities," the canal which united the Nile with the Red Sea, and the countless buildings, excavations, obelisks, colossal statues, and other great works, with which he adorned Egypt from one end to the other.