The troublous period which followed the death of Menephthah issued finally in complete anarchy, Egypt broke up into nomes, or cantons, the chiefs of which acknowledged no superior. It was as though in England, after centuries of centralized rule, the Heptarchy had suddenly returned and re-established itself. But even this was not the worst. The suicidal folly of internal division naturally provokes foreign attack; and it was not long before Aarsu, a Syrian chieftain, took advantage of the state of affairs in Egypt to extend his own dominion over one nome after another, until he had made almost the whole country subject to him. Then, at last, the spirit of patriotism awoke. Egypt felt the shame of being ruled by a foreigner of a race that she despised; and a prince was found after a time, a descendant of the Ramesside line, who unfurled the national banner, and commenced a war of independence. This prince, who bore the name of Set-nekht, or "Set the victorious," is thought by some to have been a son of Seti II., and so a grandson of Menephthah; but the evidence is insufficient to establish any such relationship. There is reason to believe that the blood of the nineteenth dynasty, of Seti I. and Ramesses II., ran in his veins; but no particular relationship to any former monarch can be made out. And certainly he owed his crown less to his descent than to his strong arm and his stout heart. It was by dint of severe fighting that he forced his way to the throne, defeating Aarsu, and gradually reducing all Egypt under his power.

Set-nekht's reign must have been short He set himself to "put the whole land in order, to execute the abominables, to set up the temples, and re-establish the divine offerings for the service of the gods, as their statutes prescribed," But he was unable to effect very much. He could not even discharge properly the main duty of a king towards himself, which was to prepare a fitting receptacle for his remains when he should quit the earth. To excavate a rock-tomb in the style fashionable at the day was a task requiring several years for its due accomplishment; Set-nekht felt that he could not look forward to many years—perhaps not even to many months—of life. In this difficulty, he felt no shame in appropriating to himself a royal tomb recently constructed by a king, named Siphthah, whom he looked upon as a usurper, and therefore as unworthy of consideration. In this sepulchre we see the names of Siphthah and his queen, Taouris, erased by the chisel from their cartouches, and the name of Set-nekht substituted in their place. By one and the same act the king punished an unworthy predecessor, and provided himself with a ready—made tomb befitting his dignity.

It was also, probably, on account of his advanced age at his accession, that he almost immediately associated in the kingdom his son Ramesses, a prince of much promise, whom he made "Chief of On," and viceroy over Lower Egypt, with Heliopolis (On) for his residence and capital. Ramesses the Third, as he is commonly called, was one of the most distinguished of Egyptian monarchs, and the last who acquired any great glory until we come down to the time of the Ethiopians, Shabak and Tirhakah. He reigned as sole monarch for thirty-one years, during the earlier portion of which period he carried on a number of important wars, while during the later portion he employed himself in the construction of those magnificent buildings, which have been chiefly instrumental in carrying his name down to posterity, and in other works of utility. Lenormant calls him "the last of the great sovereigns of Egypt," and observes with reason, that though he never ceased, during the whole time that he occupied the throne, to labour hard to re-establish the integrity of the empire abroad, and the prosperity of the country at home, yet his wars and his conquests had a character essentially defensive; his efforts, like those of the Trajans, the Marcus Aurelius's and the Septimius Severus's of history, were directed to making head against the ever rising flood of barbarians, which had already before his time burst the dykes that restrained it, and though once driven back, continued to dash itself on every side against the outer borders of the empire, and to presage its speedy overthrow. His efforts were, on the whole, successful; he was able to uphold and preserve for some considerable time longer the territorial greatness which the nineteenth dynasty had built up a second time. The monumental temple of Medinet-Abou, near Thebes, is the Pantheon erected to the glory of this great Pharaoh. Every pylon, every gateway, every chamber, relates to us the exploits which he accomplished. Sculptured compositions of large dimensions represent his principal battles.

There are times in the world's history when a restless spirit appears to seize on the populations of large tracts of country, and, without any clear cause that can be alleged, uneasy movements begin. Subdued mutterings are heard; a tremor goes through the nations, expectation of coming change stalks abroad; the air is rife with rumours; at last there bursts out an eruption of greater or less violence—the destructive flood overleaps its barriers, and flows forth, carrying devastation and ruin in one direction of another, until its energies are exhausted, or its progress stopped by some obstacle that it cannot overcome, and it subsides reluctantly and perforce. Such a time was that on which Ramesses III. was cast. Wars threatened him on every side. On his north-eastern frontier the Shasu or Bedouins of the desert ravaged and plundered, at once harrying the Egyptian territory and threatening the mining establishments of the Sinaitic region. To the north-west the Libyan tribes, Maxyes, Asbystæ, Auseis, and others, were exercising a continuous pressure, to which the Egyptians were forced to yield, and gradually a foreign population was "squatting" on the fertile lands, and driving the former possessors of the soil back upon the more eastern portion-of the Delta. "The Lubu and Mashuash," says Ramesses, "were seated in Egypt; they took the cities on the western side from Memphis as far as Karbana, reaching the Great River along its entire course (from Memphis northwards), and capturing the city of Kaukut For many years had they been in Egypt" Ramesses began his warlike operations by a campaign against the Shasu, whose country he invaded and overran, spoiling and destroying their cabins, capturing their cattle, slaying all who resisted him, and carrying back into Egypt a vast number of prisoners, whom he attached to the various temples as "sacred slaves." He then turned against the Libyans, and coming upon them unexpectedly in the tract between the Sebennytic branch of the Nile and the Canopic, he defeated in a great battle the seven tribes of the Mashuash, Lubu, Merbasat, Kaikasha, Shai, Hasa, and Bakana, slaughtering them with the utmost fury, and driving them before him across the western branch of the river. "They trembled before him," says the native historian, "as the mountain goats tremble before a bull, who stamps with his foot, strikes with his horns, and makes the mountains shake as he rushes on whoever opposes him." The Egyptians gave no quarter that memorable day. Vengeance had free course: the slain Libyans lay in heaps upon heaps—the chariot wheels passed over them—the horses trampled them in the mire. Hundreds were pushed and forced into the marshes and into the river itself, and, if they escaped the flight of missiles which followed, found for the most part a watery grave in the strong current. Ramesses portrays this flight and carnage in the most graphic way. The slain enemy strew the ground, as he advances over them with his prancing steeds and in his rattling war-car, plying them moreover with his arrows as they vainly seek to escape. His chariot force and his infantry have their share in the pursuit, and with sword, or spear, or javelin, strike down alike the resisting and the unresisting. No one seeks to take a prisoner. It is a day of vengeance and of down-treading, of fury allowed to do its worst, of a people drunk with passion that has cast off all self-restraint.

Even passion exhausts itself at last, and the arm grows weary of slaughtering. Having sufficiently revenged themselves in the great battle, and the pursuit that followed it, the Egyptians relaxed somewhat from their policy of extreme hostility. They made a large number of the Libyans prisoners, branded them with a hot iron, as the Persians often did their prisoners, and forced them to join the naval service and serve as mariners on board the Egyptian fleet. The chiefs of greater importance they confined in fortresses. The women and children became the slaves of the conquerors; the cattle, "too numerous to count," was presented by Ramesses to the Priest-College of Ammon at Thebes.

So far success had crowned his arms; and it may well be that Ramesses would have been content with the military glory thus acquired, and have abstained from further expeditions, had not he been forced within a few years to take the field against a powerful combination of new and partly unheard-of enemies. The uneasy movement among the nations, which has been already noticed, had spread further afield, and now agitated at once the coasts and islands of South-Eastern Europe, and the more western portion of Asia Minor. Seven nations banded themselves together, and resolved to unite their forces, both naval and military, against Egypt, and to attack her both by land and sea, not now on the north-western frontier, where some of them had experienced defeat before, but in exactly the opposite quarter, by way of Syria and Palestine. Of the seven, three had been among her former adversaries in the time of Menephthah, namely, the Sheklusha, the Shartana, and the Tursha; while four were new antagonists, unknown at any former period. There were, first, the Tânauna, in whom it is usual to see either the Danai of the Peloponnese, so celebrated in Homer, or the Daunii of south-eastern Italy, who bordered on the Iapyges; secondly, the Tekaru, or Teucrians, a well-known people of the Troad; thirdly, the Uashasha, who are identified with the Oscans or Ausones, neighbours of the Daunians; and fourthly, the Purusata, whom some explain as the Pelasgi, and others as the Philistines. The lead in the expedition was taken by these last. At their summons the islands and shores of the Mediterranean gave forth their piratical hordes—the sea was covered by their light galleys and swept by their strong pars—Tânauna, Shartana, Sheklusha, Tursha, and Uashasha combined their squadrons into a powerful fleet, while Purusata and Tekaru advanced in countless numbers along the land. The Purusata were especially bent on effecting a settlement; they marched into Northern Syria from Asia Minor accompanied by their wives and children, who were mounted upon carts drawn by oxen, and formed a vast unwieldy crowd. The other nations sent their sailors and their warriors without any such encumbrances. Bursting through the passes of Taurus, the combined Purusata and Tekaru spread themselves over Northern Syria, wasting and plundering the entire country of the Khita, and proceeding eastward as far as Carchemish "by Euphrates," while the ships of the remaining confederates coasted along the Syrian shore. Such resistance as the Hittites and Syrians made was wholly ineffectual. "No people stood before their arms." Aradus and Kadesh fell. The conquerors pushed on towards Egypt, anticipating an easy victory. But their fond hopes were doomed to disappointment.

Ramesses had been informed of the designs and approach of the enemy, and had had ample time to make all needful preparations. He had strengthened his frontier, called out all his best-disciplined troops, and placed the mouths of the Nile in a state of defence by means of forts, strong garrisons, and flotillas upon the stream and upon the lakes adjacent. He had selected an eligible position for encountering the advancing hordes on the coast route from Gaza to Egypt, about half-way between Raphia and Pelusium, where a new fort had been built by his orders. At this point he took his stand, and calmly awaited his enemies, not having neglected the precaution to set an ambush or two in convenient places. Here, as he kept his watch, the first enemy to arrive was the land host of the Purusata, encumbered with its long train of slowly moving bullock-carts, heavily laden with women and children. Ramesses instantly attacked them—his ambushes rose up out of their places of concealment—and the enemy was beset on every side. They made no prolonged resistance. Assaulted by the disciplined and seasoned troops of the Egyptians, the entire confused mass was easily defeated. Twelve thousand five hundred men were slain in the fight; the camp was taken; the army shattered to pieces. Nothing was open to the survivors but an absolute surrender, by which life was saved at the cost of perpetual servitude.

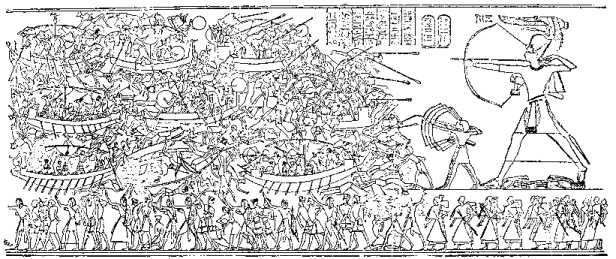

The danger, however, was as yet but half overcome—the snake was scotched but not killed. For as yet the fleet remained intact, and might land its thousands on the Egyptian coasts and carry fire and sword over the broad region of the Delta. The Tânauna and their confederates—Sheklusha, Shartana, and Tursha—made rapidly for the nearest mouth of the Nile, which was the Pelusiac, and did their best to effect a landing. But the precautions taken by Ramesses, before he set forth on his march, proved sufficient to frustrate their efforts. The Egyptian fleet met the combined squadrons of the enemy in the shallow waters of the Pelusiac lagoon, and contended with them in a fierce battle, which Ramesses caused to be represented in his sculptures—the earliest representation of a sea-fight that has come down to us. Both sides have ships propelled at once by sails and oars, but furl their sails before engaging. Each ship has a single yard, constructed to carry a single large square-sail, and hung across the vessel's single mast at a short distance below the top. The mast is crowned by a bell-shaped receptacle, large enough to contain a man, who is generally a slinger or an archer, placed there to gall the enemy with stones or arrows, and so to play the part of our own sharpshooters in the main-tops. The rowers are from sixteen to twenty-two in number, besides whom each vessel carries a number of fighting men, armed with shields, spears, swords, and bows. The fight is a promiscuous melée, the two fleets being intermixed, and each ship engaging that next to it, without a thought of combined action or of manoeuvres. One of the enemy's vessels is represented as capsized and sinking; the rest continue the engagement. Several are pressing towards the shore of the lagoon, and the men-at-arms on board them are endeavouring to effect a landing; but they are met by the land-force under Ramesses himself, who greet them with such a hail of arrows as renders it impossible for them to carry out their purpose.

SEA-FIGHT IN THE TIME OF RAMESSES III.

SEA-FIGHT IN THE TIME OF RAMESSES III.

It would seem that Ramesses had no sooner defeated and destroyed the army of the Purusata and Tekaru than he set off in haste for Pelusium, and marched with such speed as to arrive in time to witness the naval engagement, and even to take a certain part in it. The invading fleet was so far successful as to force its way through the opposing vessels of the Egyptians, and to press forward towards the shore; but here its further progress was arrested. "A wall of iron," says Ramesses, "shut them in upon the lake," The best troops of Egypt lined the banks of the lagoon, and wherever the invaders attempted to land they were foiled. Repulsed, dashed to the ground, hewn down or shot down at the edge of the water, they were slain "by hundreds of heaps of corpses." "The infantry," says the monarch in his vainglorious inscription, set up in memory of the event, "all the choicest troops of the army of Egypt, stood upon the bank, furious as roaring lions; the chariot force, selected from among the heroes that were quickest in battle, was led by officers confident in themselves. The war-steeds quivered in all their limbs, and burned to trample the nations under their feet. I myself was like the god Mentu, the warlike; I placed myself at their head, and they saw the achievements of my hands. I, Ramesses the king, behaved as a hero who knows his worth, and who stretches out his arm over his people in the day of combat. The invaders of my territory will gather no more harvests upon the earth, their life is counted to them as eternity. Those that gained the shore, I caused to fall at the water's edge, they lay slain in heaps; I overturned their vessels; all their goods sank In the waves." After a brief combat, all resistance ceased. The empty ships, floating at random upon the still waters of the lagoon, or stuck fast in the Nile mud, became the prize of the victors, and were found to contain a rich booty. Thus ended this remarkable struggle, in which nations widely severed and of various bloods—scarcely, as one would have thought, known to each other, and separated by a diversity of interests—united in an attack upon the foremost power of the known world, traversed several hundreds of miles of land or sea successfully, neither quarrelling among themselves nor meeting with disaster from without, and reached the country which they had hoped to conquer, but were there completely defeated and repulsed in two engagements—one by land, the other partly by land and partly by sea—so that "their spirit was annihilated, their soul was taken from them." Henceforth no one of the nations which took part in the combined attack is found in arms against the power that had read them so severe a lesson.

It was not long after repulsing this attack upon the independence of Egypt that Ramesses undertook his "campaign of revenge." Starting with a fleet and army along the line that his assailants had followed, he traversed Palestine and Syria, hunting the lion in the outskirts of Lebanon, and re-establishing for a time the Egyptian dominion over much of the region which had been formerly held in subjection by the great monarchs of the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties. He claims to have carried his arms to Aleppo and Carchemish, in which case we must suppose that he defeated the Hittites, or else that they declined to meet him in the field; and he gives a list of thirty-eight conquered countries or tribes, which are thought to belong to Upper Syria, Southern Asia Minor, and Cyprus. In some of his inscriptions he even speaks of having recovered Naharaina, Kush, and Punt; but there is no evidence that he really visited—much less conquered—these remote regions.

The later life of Ramesses III. was, on the whole a time of tranquillity and repose. The wild tribes of North Africa, after one further attempt to establish themselves in the western Delta, which wholly failed, acquiesced in the lot which nature seemed to have assigned them, and, leaving the Egyptians in peace, contented themselves with the broad tract over which they were free to rove between the Mediterranean and the Sahara Desert. On the south Ethiopia made no sign. In the east the Hittites had enough to do to rebuild the power which had been greatly shattered by the passage of the hordes of Asia Minor through their territory, on their way to Egypt and on their return from it. The Assyrians had not yet commenced their aggressive wars towards the north and west, having probably still a difficulty in maintaining their independence against the attacks of Babylon. Egypt was left undisturbed by her neighbours for the space of several generations, and herself refrained from disturbing the peace of the world by foreign expeditions. Ramesses turned his attention to building, commerce, and the planting of Egypt with trees. He constructed and ornamented the beautiful temple of Ammon at Medinet-Abou, built a fleet on the Red Sea and engaged in trade with Punt, dug a great reservoir in the country of Aina (Southern Palestine), and "over the whole land of Egypt planted trees and shrubs, to give the inhabitants rest under their cool shade."

The general decline of Egypt must, however, be regarded as having commenced in his reign. His Eastern conquests were more specious than solid, resulting in a nominal rather than a real subjection of Palestine and Syria to his yoke. His subjects grew unaccustomed to the use of arms during the last twenty, or five and twenty, years of his life. Above all, luxury, intrigue, and superstition invaded the court, where the eunuchs and concubines exercised a pernicious influence. Magic was practised by some of the chief men in the State, and the belief was widely spread that it was possible by charms, incantations, and the use of waxen images, to bewitch men, or paralyse their limbs, or even to cause their deaths. Hags were to be found about the court as wicked as Canidia, who were willing to sell their skill in the black art to the highest bidder. The actual person of the monarch was not sacred from the plottings of this nefarious crew, who planned assassinations and hatched conspiracies in the very purlieus of the royal palace. Ramesses himself would, apparently, have fallen a victim to a plot of the kind, had not the parties to it been discovered, arrested, tried by a Royal Commission, and promptly executed.

The descendants of Ramesses III. occupied the throne from his death (about B.C. 1280) to B.C. 1100. Ten princes of the name of Ramesses, and one called Meri-Tum, bore sway during this interval, each of them showing, if possible, greater weakness than the last, and all of them sunk in luxury, idle, effeminate, sensual. Ramesses III. provoked caricature by his open exhibition of harem-scenes on the walls of his Medinet-Abou palace. His descendants, content with harem life, scarcely cared to quit the precincts of the royal abode, desisted from all war, and even devolved the task of government on other shoulders. The Pharaohs of the twentieth dynasty became absolute fainéants, and devolved their duties on the high-priests of the great temple of Ammon at Thebes, who "set themselves to play the same part which at a distant period was played by the Mayors of the Palace under the later French kings of the Merovingian line."

In an absolute monarchy, the royal authority is the mainspring which controls all movements and all actions in every part of the State. Let this source of energy grow weak, and decline at once shows itself throughout the entire body politic. It is as when a fatal malady seizes on the seat of life in an individual—instantly every member, every tissue, falls away, suffers, shrinks, decays, perishes. Egyptian architecture is simply non-existent from the death of Ramesses III. to the age of Sheshonk; the "grand style" of pictorial art disappears; sculpture in relief becomes a wearisome repetition of the same stereotyped religious groups; statuary deteriorates and is rare; above all, literature declines, undergoing an almost complete eclipse. A galaxy of literary talent had, as we have seen, clustered about the reigns of Ramesses II. and Menephthah, under whose encouragement authors had devoted themselves to history, divinity, practical philosophy, poetry, epistolary correspondence, novels, travels, legend. From the time of Ramesses III.—nay, from the time of Seti II.—all is a blank: "the true poetic inspiration appears to have vanished," literature is almost dumb; instead of the masterpieces of Pentaour, Kakabu, Nebsenen, Enna, and others, which even moderns can peruse with pleasure, we have only documents in which "the dry official tone" prevails—abstracts of trials, lists of functionaries, tiresome enumerations in the greatest detail of gifts made to the gods, together with fulsome praises of the kings, written either by themselves or by others, which we are half inclined to regret the lapse of ages has spared from destruction. At the same time morals fall off. Sensuality displays itself in high places. Intrigue enters the charmed circle of the palace. The monarch himself is satirized in indecent drawings. Presently, the whole idea of a divinity hedging in the king departs; and a "thieves' society" is formed for rifling the royal tombs, and tearing the jewels, with which they have been buried, from the monarchs' persons. The king's life is aimed at by conspirators, who do not scruple to use magical arts; priests and high judicial functionaries are implicated in the proceedings. Altogether, the old order seems to be changed, the old ideas to be upset; and no new principles, possessing any vital efficacy, are introduced. Society gradually settles upon its lees; and without some violent application of force from without, or some strange upheaval from within, the nation seems doomed to fall rapidly into decay and dissolution.

CARICATURE OF THE TIME OF RAMESSES III.

CARICATURE OF THE TIME OF RAMESSES III.