The rise of the twenty-second resembles in many respects that of the twenty-first dynasty. In both cases the cause of the revolution Is to be found in the weakness of the royal house, which rapidly loses its pristine vigour, and is impotent to resist the first assault made upon it by a bold aggressor. Perhaps the wonder is rather that Egyptian dynasties continued so long as they did, than that they were not longer-lived, since there was in almost every instance a rapid decline, alike in the physique and in the mental calibre of the holders of sovereignty; so that nothing but a little combined strength and audacity was requisite in order to push them from their pedestals. Shishak was an official of a Semitic family long settled in Egypt, which had made the town of Bubastis its residence. We may suspect, if we like, that the family had noble—shall we say royal?—blood in its veins, and could trace its descent to dynasties which had ruled at Nineveh or Babylon. The connexion is possible, though scarcely probable, since no éclat attended the first arrival of the Shishak family In Egypt, and the family names, though Semitic, are decidedly neither Babylonian nor Assyrian. It is tempting to adopt the sensational views of writers, who, out of half a dozen names, manufacture an Assyrian conquest of Egypt, and the establishment on the throne of the Pharaohs of a branch derived from one or other of the royal Mesopotamian houses; but "facts are stubborn things," and the imagination is scarcely entitled to mould them at its will. It is necessary to face the two certain facts—(1) that no one of the dynastic names is the natural representative of any name known to have been borne by any Assyrian or Babylonian; and (2) that neither Assyria nor Babylonia was at the time in such a position as to effect, or even to contemplate, distant enterprizes. Babylonia did not attain such a position till the time of Nabopolassar; Assyria had enjoyed it about B.C. 1150-1100, but had lost it, and did not recover it till B.C. 890. Moreover, Solomon's empire blocked the way to Egypt against both countries, and required to be shattered in pieces before either of the great Mesopotamian powers could have sent a corps d'armée into the land of the Pharaohs.

Sober students of history will therefore regard Shishak (Sheshonk) simply as a member of a family which, though of foreign extraction, had been long settled in Egypt, and had worked its way into a high position under the priest-kings of Herhor's line, retaining a special connection with Bubastis, the place which it had from the first made its home. Sheshonk's grandfather, who bore the same name; had had the honour of intermarrying into the royal house, having taken to wife Meht-en-hont, a princess of the blood whose exact parentage is unknown to us. His father Namrut, had held a high military office, being commander of the Libyan mercenaries, who at this time formed the most important part of the standing army. Sheshonk himself, thus descended, was naturally in the front rank of Egyptian court-officials. When we first hear of him he is called "His Highness," and given the title of "Prince of the princes," which is thought to imply that he enjoyed the first rank among all the chiefs of mercenaries, of whom there were many. Thus he held a position only second to that occupied by the king, and when his son became a suitor for the hand of a daughter of the reigning sovereign, no one could say that etiquette was infringed, or an ambition displayed that was excessive and unsuitable. The match was consequently allowed to come off, and Sheshonk became doubly connected with the royal house, through his daughter-in-law and through his grandmother. When, therefore, on the death of Hor-pa-seb-en-sha, he assumed the title and functions of king, no opposition was offered: the crown seemed to have passed simply from one member of the royal family to another.

In monarchies like the Egyptian, it is not very difficult for an ambitious subject, occupying a certain position, to seize the throne; but it is far from easy for him to retain it Unless there is a general impression of the usurper's activity, energy, and vigour, his authority is liable to be soon disputed, or even set at nought It behoves him to give indications of strength and breadth of character, or of a wise, far-seeing policy, in order to deter rivals from attempting to undermine his power. Sheshonk early let it be seen that he possessed both caution and far-reaching views by his treatment of a refugee who, shortly after his accession, sought his court. This was Jeroboam, one of the highest officials in the neighbouring kingdom of Israel, whom Solomon, the great Israelite monarch, regarded with suspicion and hostility, on account of a declaration made by a prophet that he was at some future time to be king of Ten Tribes out of the Twelve. To receive Jeroboam with favour was necessarily to offend Solomon, and thus to reverse the policy of the preceding dynasty, and pave the way for a rupture with the State which was at this time Egypt's most important neighbour. Sheshonk, nevertheless, accorded a gracious reception to Jeroboam; and the favour in which he remained at the Egyptian court was an encouragement to the disaffected among the Israelites, and distinctly foreshadowed a time when an even bolder policy would be adopted, and a strike made for imperial power. The time came at Solomon's demise. Jeroboam was at once allowed to return to Palestine, and to foment the discontent which it was foreseen would terminate in separation. The two kings had, no doubt, laid their plans. Jeroboam was first to see what he could effect unaided, and then, if difficulty supervened, his powerful ally was to come to his assistance. For the Egyptian monarch to have appeared in the first instance would have roused Hebrew patriotism against him. Sheshonk waited till Jeroboam had, to a certain extent, established his kingdom, had set up a new worship blending Hebrew with Egyptian notions, and had sufficiently tested the affection or disaffection towards his rule of the various classes of his subjects. He then marched out to his assistance. Levying a force of twelve hundred chariots, sixty thousand horse (? six thousand), and footmen "without number" (2 Chron, xii. 3), chiefly from the Libyan and Ethiopian mercenaries which now formed the strength of the Egyptian armies, he proceeded into the Holy Land, entering it "in three columns," and so spreading his troops far and wide over the southern country. Rehoboam, Solomon's son and successor, had made such preparation as was possible against the attack. He had anticipated it from the moment of Jeroboam's return, and he had carefully guarded the main routes whereby his country could be approached from the south, fortifying, among other cities, Shoco, Adullam, Azekah, Gath, Mareshah, Ziph, Tekoa, and Hebron (2 Chron. xi. 6-10). But the host of Sheshonk was irresistible. Never before had the Hebrews met in battle the forces of their powerful southern neighbour—never before had they been confronted with huge masses of disciplined troops, armed and trained alike, and soldiers by profession. The Jewish levies were a rude and untaught militia, little accustomed to warfare, or even to the use of arms, after forty years of peace, during which "every man had dwelt safely under the shade of his own vine and his own fig-tree" (1 Kings iv. 25). They must have trembled before the chariots, and cavalry, and trained footmen of Egypt. Accordingly, there seems to have been no battle, and no regularly organized resistance. As the host of Sheshonk advanced along the chief roads that led to the Jewish capital, the cities, fortified with so much care by Rehoboam, either opened their gates to him, or fell after brief sieges (2 Chron. xii. 4). Sheshonk's march was a triumphal progress, and in an incredibly short space of time he appeared before Jerusalem, where Rehoboam and "the princes of Judah" were tremblingly awaiting his arrival. The son of Solomon surrendered at discretion; and the Egyptian conqueror entered the Holy City, stripped the Temple of its most valuable treasures, including the shields of gold which Solomon had made for his body-guard, and plundered the royal palace (2 Chron, xii. 9). The city generally does not appear to have been sacked: nor was there any massacre. Rehoboam's submission was accepted; he was maintained in his kingdom; but he had to become Sheshonk's "servant" (2 Chron. xii. 8), i.e., he had to accept the position of a tributary prince, owing fealty and obedience to the Egyptian monarch.

The objects of Sheshonk's expedition were-not yet half accomplished. By the long inscription which he set up on his return to Egypt, we find that, after having made Judea subject to him, he proceeded with his army into the kingdom of Israel, and there also took a number of towns which were peculiarly circumstanced. The Levites of the northern kingdom had from the first disapproved of the religious changes effected by Jeroboam; and the Levitical cities within his dominions were regarded with an unfriendly eye by the Israelite monarch, who saw in them hotbeds of rebellion. He had not ventured to make a direct attack upon them himself, since he would thereby have lighted the torch of civil war within his own borders; but, having now an Egyptian army at his beck and call, he used the foreigners as an instrument at once to free him from a danger and to execute his vengeance upon those whom he looked upon as traitors. Sheshonk was directed or encouraged to attack and take the Levitical cities of Rehob, Gibeon, Mahanaim, Beth-horon, Kedemoth, Bileam or Ibleam, Alemoth, Taanach, Golan, and Anem, to plunder them and carry off their inhabitants as slaves; while he was also persuaded to reduce a certain number of Canaanite towns, which did not yield Jeroboam a very willing obedience. We may trace the march of Sheshonk by Megiddo, Taanach, and Shunem, to Beth-shan, and thence across the Jordan to Mahanaim and Aroer; after which, having satisfied his vassal, Jeroboam, he proceeded to make war on his own account with the Arab tribes adjoining on Trans-Jordanic Israel, and subdued the Temanites, the Edomites, and various tribes of the Hagarenes. His dominion was thus established from the borders of Egypt to Galilee, and from the Mediterranean to the Great Syrian Desert.

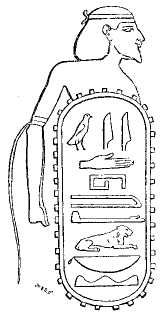

On his return to Egypt from Asia, with his prisoners and his treasures, it seemed to the victorious monarch that he might fitly follow the example of the old Pharaohs who had made expeditions into Palestine and Syria, and commemorate his achievements by a sculptured record. So would he best impress the mass of the people with his merits, and induce them to put him on a par with the Thothmeses and the Amenhoteps of former ages. On the southern external wall of the great temple of Karnak, he caused himself to be represented twice—once as holding by the hair of their heads thirty-eight captive Asiatics, and threatening them with uplifted mace; and a second time as leading captive one hundred and thirty-three cities or tribes, each specified by name and personified in an individual form, the form, however, being incomplete. Among these representations is one which bears the inscription "Yuteh Malek," and which must be regarded as figuring the captive Judæan kingdom.

FIGURE RECORDING THE CONQUEST OF JUDÆA BY SHISHAK.

FIGURE RECORDING THE CONQUEST OF JUDÆA BY SHISHAK.

Thus, after nearly a century and a half of repose, Egypt appeared once more in Western Asia as a conquering power, desirious of establishing an empire. The political edifice raised with so much trouble by David, and watched over with such care by Solomon, had been shaken to its base by the rebellion of Jeroboam; it was shattered beyond all hope of recovery by Shishak. Never more would the fair fabric of an Israelite empire rear itself up before the eyes of men; never more would Jerusalem be the capital of a State as extensive as Assyria or Babylonia, and as populous as Egypt. After seventy years, or so, of union, Syria was broken up—the cohesion effected by the warlike might of David and the wisdom of Solomon ceased—the ill-assimilated parts fell asunder; and once more the broad and fertile tract intervening between Assyria and Egypt became divided among a score of petty States, whose weakness invited a conqueror.

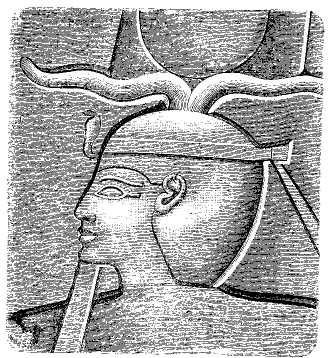

HEAD OF SHISHAK

HEAD OF SHISHAK

Sheshonk did not live many years to enjoy the glory and honour brought him by his Asiatic successes. He died after a reign of twenty-one years, leaving his crown to his second son, Osorkon, who was married to the Princess Keramat, a daughter of Sheshonk's predecessor. The dynasty thus founded continued to occupy the Egyptian throne for the space of about two centuries, but produced no other monarch of any remarkable distinction. The Asiatic dominion, which Sheshonk had established, seems to have been maintained for about thirty years, during the reigns of Osorkon L, Sheshonk's son, and Takelut I., his grandson; but in the reign of Osorkon II., the son of Takelut, the Jewish monarch of the time, Asa, the grandson of Rehoboam, shook off the Egyptian yoke, re-established Judæan independence, and fortified himself against attack by restoring the defences of all those cities which Sheshonk had dismantled, and "making about them walls, and towers, gates, and bars" (2 Chron. xiv. 7). At the same time he placed under arms the whole male population of his kingdom, which is reckoned by the Jewish historian at 580,000 men. The "men of Judah" bore spears and targets, or small round shields; the "men of Benjamin" had shields of a larger size, and were armed with the bow (ib. ver. 8). "All these," says the historian, "were mighty men of valour." It was not to be supposed that Egypt would bear tamely this defiance, or submit to the entire loss of her Asiatic dominion, which was necessarily involved in the revolt of Judæa, without an effort to retain it. Osorkon II., or whoever was king at the time, rose to the occasion. If it was to be a contest of numbers, Egypt should show that she was certainly not to be outdone numerically; so more mercenaries than ever before were taken into pay, and an army was levied, which is reckoned at "a thousand thousand" (ib. ver. 9), consisting of Cushites or Ethiopians, and of Lubim (ib. xvi. 8), or natives of the North African coast-tract, With these was sent a picked force of three hundred war-chariots, probably Egyptian; and the entire host was placed under the command of an Ethiopian general, who is called Zerah. The host set forth from Egypt, confident of victory, and proceeded as far as Mareshah in Southern Judæa, where they were met by the undaunted Jewish king. What force he had brought with him is uncertain, but the number cannot have been very great. Asa had recourse to prayer, and, in words echoed in later days by the great Maccabee (1 Mac. iii. 18, 19), besought Jehovah to help him against the Egyptian "multitude." Then the two armies joined battle; and, notwithstanding the disparity of numbers, Zerah was defeated. "The Ethiopians and the Lubim, a huge host, with very many chariots and horsemen" (2 Chron. xvi. 8) fled before Judah—they were "overthrown that they could not recover themselves, and were destroyed before Jehovah and before His host" (ib. xiv. 13). The Jewish troops pursued them as far as Gerar, smiting them with a great slaughter, taking their camp? and loading themselves with spoil. What became of Zerah we are not told. Perhaps he fell in the battle; perhaps he carried the news of his defeat to his Egyptian master, and warned him against any further efforts to subdue a people which could defend itself so effectually.

The direct effect of the victory of Asa was to put an end, for three centuries, to those dreams of Asiatic dominion which had so long floated before the eyes of Egyptian kings, and dazzled their imaginations. If a single one of the petty princes between whose rule Syria was divided could defeat and destroy the largest army that Egypt had ever brought into the field, what hope was there of victory over twenty or thirty of such chieftains? Henceforth, until the time of the great revolution brought about in Western Asia through the destruction of the Assyrian Empire by the Medes, the eyes of Egypt were averted from Asia, unless when attack threatened her. She shrank from provoking the repetition of such a defeat as Zerah had suffered, and was careful to abstain from all interference with the affairs of Palestine, except on invitation. She learnt to look upon the two Israelite kingdoms as her bulwarks against attack from the East, and it became an acknowledged part of her policy to support them against Assyrian aggression. If she did not succeed in rendering them any effective assistance, it was not for lack of good-will. She was indeed a "bruised reed" to lean upon, but it was because her strength was inferior to that of the great Mesopotamian power.

From the time of Osorkon II., the Sheshonk dynasty rapidly declined in power. A system of constituting appanages for the princes of the reigning house grew up, and in a short time conducted the country to the verge of dissolution. "For the purpose of avoiding usurpations analogous to that of the High-Priests of Ammon," says M. Maspero, "Sheshonk and his descendants made a rule to entrust all positions of importance, whether civil or military, to the princes of the blood royal. A son of the reigning Pharaoh, most commonly his eldest son, held the office of High-Priest of Ammon and Governor of Thebes; another commanded at Sessoun (Hermopolis); another at Hakhensu, others in all the large towns of the Delta and of Upper Egypt. Each of them had with him several battalions of those Libyan soldiers—Matsiou and Mashuash—who formed at this time the strength of the Egyptian army, and on whose fidelity it was always safe to count. Ere long these commands became hereditary, and the feudal system, which had anciently prevailed among the chiefs of nomes or cantons, re-established itself for the advantage of the members of the reigning house. The Pharaoh of the time continued to reside at Memphis, or at Bubastis, to receive the taxes, to direct as far as was possible the central administration, and to preside at the grand ceremonies of religion, such as the enthronement or the burial of an Apis-Bull; but, in point of fact, Egypt found itself divided into a certain number of principalities, some of which comprised only a few towns, while others extended over several continuous cantons. After a time the chiefs of these principalities were emboldened to reject the sovereignty of the Pharaoh altogether; relying on their bands of Libyan mercenaries, they usurped, not only the functions of royalty, but even the title of king, while the legitimate dynasty, cooped up in a corner of the Delta, with difficulty preserved a certain remnant of authority."

Upon disintegration followed, as a natural consequence, quarrel and disturbance. In the reign of Takelut II., the grandson of Osorkon II., troubles broke out both in the north and in the south. Takelut's eldest son, Osorkon, who was High-Priest of Ammon, and held the government of Thebes and the other provinces of the south, was only able to maintain the integrity of the kingdom by means of perpetual civil wars. Under his successors, Sheshonk III., Pamai, and Sheshonk IV., the revolts became more and more serious. Rival dynasties established themselves at Thebes, Tanis, Memphis, and elsewhere. Ethiopia grew more powerful as Egypt declined, and threatened ere long to establish a preponderating influence over the entire Nile valley. But the Egyptian princes were too jealous of each other to appreciate the danger which threatened them. A very epidemic of decentralization set in; and by the middle of the eighth century, just at the time when Assyria was uniting together and blending into one all the long-divided tribes and nations of Western Asia, Egypt suicidally broke itself up into no fewer than twenty governments!

Such a condition of things was, of course, fatal to literature and art. Art, as has been said, "did not so much decline as disappear." After Sheshonk I. no monarch of the line left any building or sculpture of the slightest importance. The very tombs became unpretentious, and merely repeated antique forms without any of the antique spirit. Each Apis, indeed, had, in his turn, his arched tomb cut for him in the solid rock of the Serapeum at Memphis, and was laid to rest in a stone sarcophagus, formed of a single block. A stela, moreover, was in every case inscribed and set up to his memory: but the stelæ were rude memorials, devoid of all artistic taste; the tombs were mere reproductions of old models; and the inscriptions were of the dullest and most prosaic kind. Here is one, as a specimen: "In the year 2, the month Mechir, on the first day of the month, under the reign of King Pimai, the god Apis was carried to his rest in the beautiful region of the west, and was laid in the grave, and deposited in his everlasting house and his eternal abode. He was born in the year 28, in the time of the deceased king, Sheshonk III. His glory was sought for in all places of Lower Egypt. He was found after some months in the city of Hashedabot. He was solemnly introduced into the temple of Phthah, beside his father—the Memphian god Phthah of the south wall—by the high-priest in the temple of Phthah, the great prince of the Mashuash, Petise, the son of the high-priest of Memphis and great prince of the Mashuash, Takelut, and of the princess of royal race, Thes-bast-per, in the year 28, in the month of Paophi, on the first day of the month. The full lifetime of this god amounted to twenty-six years." Such is the historical literature of the period. The only other kind of literature belonging to it which has come down to us, consists of what are called "Magical Texts." These are to the following effect:—"When Horns weeps, the water that falls from his eyes grows into plants producing a sweet perfume. When Typhon lets fall blood from his nose, it grows into plants changing to cedars, and produces turpentine instead of the water. When Shu and Tefnut weep much, and water falls from their eyes, it changes into plants that produce incense. When the Sun weeps a second time, and lets water fall from his eyes, it is changed into working bees; they work in the flowers of each kind, and honey and wax are produced instead of the water. When the Sun becomes weak, he lets fall the perspiration of his members, and this changes to a liquid." Or again—"To make a magic mixture: Take two grains of incense, two fumigations, two jars of cedar-oil, two jars of tas, two jars of wine, two jars of spirits of wine. Apply it at the place of thy heart. Thou art protected against the accidents of life; thou art protected against a violent death; thou art protected against fire; thou art not ruined on earth, and thou escapest in heaven."